The Integrated Man

We're All Severed

* Warning: I’m going to be telling a very difficult story at the beginning of this essay. It involves the traumatic untimely loss of a loved one. If you’re not in the right headspace for digesting that today, I would ask that you skip this one. - Chance

The Exhaustion of Multiple Selves

Long before I would become successful in sales, before I would have trouble selling my business (wait, I bought a business?) and therefore get my real estate license in order to join a business brokerage, and well before I would get laid off and strike out to become a business coach, I was going to be Dr. Sweat.

Which sounds more like something you apply to manage athlete’s foot than the name of a serious doctor.

I wanted to be an ER Doctor. I loved the idea of orthopedics, but I wanted some resemblance of a normal schedule, low chance of on-call, and I didn’t want to deal with patient follow ups. I wanted to do some procedures, have some hectic and crazy moments, be able to tell some great stories, yet be able to “clock out” at the end of the day.

In college I was pursuing a degree in Biology, which I did get, and working in the Emergency Room on the days and nights that I didn’t have class or lab.

One of my most vivid images burned into my brain was Mother’s Day 2015.

The scene belonged in an episode of Grey’s Anatomy. Towards the end of the shift, packaging up charts and preparing to turn over to the night shift when someone yelled “WE NEED THE DOCTOR!”

I turned around to find a gurney being raced into room 3, right off the ambulance bay, with my mother on top of a patient doing chest compressions (don’t worry she was an ER Nurse at the time).

Intubation, IV’s, bags of fluid, life saving medications, ice packs, the ER Staff threw everything at this kid. He was 18, if I remember correctly, and collapsed on the field near the hospital playing soccer with his friends. Out of pure terror they threw him in the car and rushed him to the hospital about a mile away.

We did compressions for over an hour. In my 3, maybe it was 4, years in the ER at the time I had seen a lot of death. My first night ever out of training our first patient was a young lady that had hung herself because her boyfriend wouldn’t leave his wife for her.

I sat in my car and cried for an hour after that shift.

In nearly the half a decade I had spent witnessing and documenting these moments, I had never seen the doctor do this though. He turned to each person in the room and asked what they wanted to do. I didn’t have an answer for him, I was too choked up seeing myself on that gurney. Everyone said that it was time to call it, we had been working for over an hour and there were no signs of life, no signs of any brain activity.

However, one nurse asked for a few more minutes, and the doctor obliged, no one argued with her, they continued with the chaotic ballet that was a code.

Ten minutes later the doctor called the time of death, and brought the parents in and told them their son was gone. I remember the father swinging at the doctor, the paramedics having to restrain him. That night I walked to my car, swung through Starbucks for a frozen coffee treat. I listened to music and drove with the windows down.

I didn’t shed a tear.

In some ways I realized then that I was broken at the time. I had compartmentalized my work in order to not let it affect me, in order to not let it suck the life out of every other area of my life. The doctor I worked with that night is one of the greatest men I know, and one of the most caring, but I came to realize over the coming year that I couldn’t do this with my life. I did not want to be this jaded to trauma. I didn’t want to be a guy that could witness what I witnessed and treat myself to something like I had a long day answering emails.

The Cost of Compartmentalization

I thought I was protecting myself at the time. Building walls between the ER and everything else. Work stays at work, home stays at home, church stays at church (I wasn’t going to church then but you get it).

Neat little boxes. Clean separation. The problem is that when you build walls inside yourself, you’re not actually protecting anything, you’re fracturing everything else about you.

That drive home from the hospital wasn’t actually peaceful. It was numbness masquerading as composure. Windows down, music up, pretending that watching an 18-year-old die and then ordering a caramel Frappuccino was somehow normal human behavior. It wasn’t strength. It was survival mode.

Survival mode is a terrible long-term strategy for actually living.

Here’s what I didn’t understand then, and I’m only now coming to realize in my 30’s, compartmentalization doesn’t contain the damage, it spreads a different type of damage instead.

You can’t turn off your capacity to feel in one room and expect it to magically reappear in another. The callousness I needed to walk out of that ER without breaking down wasn’t something I could just leave at the hospital. I brought it home. I brought it to dinner with friends. I brought it to school. I became fluent in surface-level conversation because going deep required accessing parts of myself I’d locked away for self-preservation.

We tell ourselves we’re being professional. Appropriate. That different contexts require different versions of ourselves. And there is truth in that. You probably shouldn’t crack the same jokes with your kids that you do with your adult friends. But there’s a massive difference between adjusting your delivery and fundamentally changing who you are.

It’s exhausting. Not just for the people around you, but for you. Because maintaining multiple versions of yourself requires constant code-switching, constant performance, constant energy expenditure on just trying to remember which mask you’re supposed to be wearing in which room.

And here’s what I learned after getting laid off, you start losing track of which version is actually you.

When I was working in that ER, I thought I was protecting my “real self” by not letting the job touch it. The truth is I was eroding my real self by practicing disconnection as a daily discipline. Every shift where I chose numbness over feeling, efficiency over empathy, I was training myself in fragmentation.

The version of me that could do that wasn’t some professional alter ego I put on with my uniform. It was becoming me. And the scarier part? I was starting to need that fragmentation. Because if I let myself actually feel what I was seeing in that ER, I’d have to make a choice about whether this was really how I wanted to spend my life. Compartmentalization wasn’t just protecting me from the job, it was protecting me from having to make hard decisions about my life.

Roosevelt said, “In any moment of decision, the best thing you can do is the right thing, the next best thing is the wrong thing, and the worst thing you can do is nothing.”

Compartmentalization is choosing nothing. It’s deciding that instead of integrating hard experiences into your life and making decisions based on who you actually are, you’ll just create different versions of yourself for different contexts and never have to decide anything.

That 18-year-old’s father swinging at the doctor wasn’t irrational. It was the most human thing that happened that entire night. He was feeling everything all at once, grief, rage, helplessness, love, without any walls or compartments or professional distance. He was integrated, even in his breaking. And I walked out to my car and felt nothing.

That’s the real cost. Not just the energy it takes to maintain the performance. The slow erosion of your ability to be fully human in any room.

What Integration Actually Looks Like

Integration isn’t about being the same in every situation. It’s about being yourself in every situation. That’s a huge difference.

You’re going to be different with your five-year-old than you are in a business negotiation. That’s not duplicity, that’s called not being a sociopath. Your tone will change, your vocabulary will change, your energy will adjust to the context. But the core of who you are, your values, your character, your way of moving through the world, that stays consistent.

Think about the best men you know. The ones you actually respect, not just admire from a distance. They have range. They can be serious when it matters and ridiculous when it doesn’t. They can lead a meeting and coach a soccer team and have a difficult conversation with their wife, and somehow they’re recognizably the same person in all of it. That’s not because they’re performing consistency, it’s because they’ve done the work of actually integrating who they are.

Anthony Bourdain understood this. Watch any episode of his shows and he’s the same guy whether he’s eating street food in Vietnam or sitting across from Obama. Curious, honest, respectful, occasionally profane, always real. He didn’t code-switch based on who was in the room. He adapted his approach while maintaining his essence. That’s the difference.

When I left the ER and eventually found my way into sales, I learned this the hard way. Early on I tried to be “professional” in the way I thought you were supposed to be professional. Measured. Careful. Presenting the version of myself I thought clients wanted to see. And it was exhausting and ineffective in equal measure. No wonder I would log off and doomscroll for hours. I was spent.

I spent my twenties living segmented. Code-switching like it was an Olympic sport. ER Chance was calm, clinical, efficient, nothing got through. Corporate Chance was polished, rehearsed, whatever the client needed me to be. Home Chance was... honestly, I’m not even sure who that guy was supposed to be.

I thought I was being sophisticated. Mature. Professional. What I was actually doing was fracturing myself into pieces and calling it success.

It worked for a while. Or at least I thought it did. I climbed the ladder at my company, hit my numbers, built a reputation, tons of friendships. Nearly nine years of performing, compartmentalizing, keeping all the different versions of myself in their proper boxes. And then they laid me off.

That afternoon hit different than I expected. I thought I’d be angry, or scared, or worried about finances. But in the week and a half since, I realized that I was actually mourning. Not for the job, but for the piece of Chance that I’d left in that company. The version of myself I’d built over nine years that no longer had anywhere to exist.

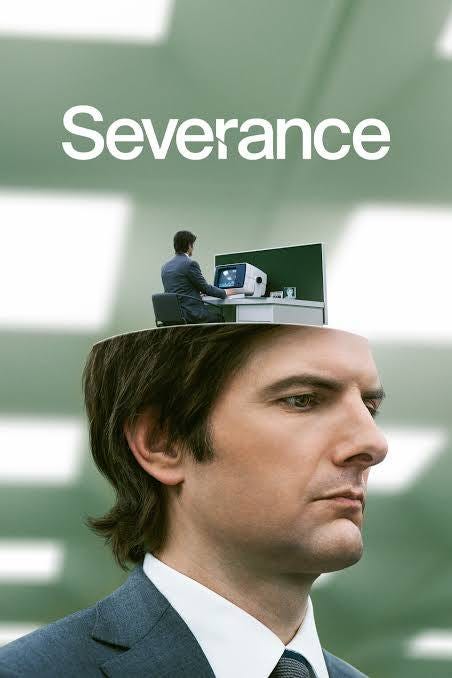

Have you watched the show Severance yet? Where they split your work self from your real self, except I’d done it voluntarily to every area of my life. And now one of those selves had just been deleted, and I was supposed to figure out who was left.

I lost the plot I discovered in that ER. That numbness I felt walking out after the 18-year-old died wasn’t strength or professionalism, it was the beginning of my own fragmentation. I’d learned to disconnect, to separate, to keep parts of myself isolated from other parts. And I’d gotten so good at it that I’d forgotten how to be whole.

The layoff forced me to confront something I’d been avoiding, who was I when I wasn’t performing for anyone?

Curious if you’re severed? Ask yourself: What would you do if no one were watching? What would you do if everyone were watching? If those answers are substantially different, you’ve got work to do.

I’m not talking about the dumb stuff. Obviously you might scratch different places in private than in public (too bold?). I’m talking about character decisions. How you treat people. What you’re willing to compromise on. Whether you keep your word. Do you eat the cookie or don’t you? If those things change based on who’s in the room, you’re not integrated, you’re just performing different versions of morality for different audiences.

Integration means your private self and your public self are having the same conversation. The way you talk about your struggles is the same whether you’re with your men’s group or in a business meeting, honest about the difficulty, committed to growth, not pretending you have it all figured out. The way you treat people is consistent whether they can do something for you or not. The standards you hold yourself to don’t fluctuate based on whether anyone’s checking.

This doesn’t mean oversharing your personal life in inappropriate contexts. I’m not suggesting you process your marriage struggles with your clients or lead with your trauma in every conversation. Context matters. But there’s a massive difference between having appropriate boundaries and having different operating systems for different parts of your life.

If my kids were old enough to understand what a layoff was, I’d tell them the truth. Not all the details, but the truth. If it’s been a hard week, I say it’s been a hard week. They see me as someone who works hard at something that matters, not some mysterious figure who transforms into a different person when he leaves the house. And when they see me at church, or coaching their teams, or having dinner with friends, they should see the same person.

Your values are your operating system, not your persona. The same code runs different applications. Honesty, integrity, service, courage, those don’t change based on whether you’re in a boardroom or at a barbecue. How you express them will change. But the core commitments stay consistent.

That’s integration. Not sameness. Coherence.

The Christian Integration

If you’re a Christian, your faith shouldn’t be a Sunday supplement to your real life. It’s not a hobby you pick up once a week between work and golf. It’s supposed to be the foundational architecture. The operating system we were just talking about. And if it’s not functioning that way, you need to ask yourself some hard questions about whether you actually believe any of it.

I’m not talking about being the guy who leads every conversation with a Bible verse or finds a way to mention Jesus in every business meeting. That’s not faith integration, that’s awkward evangelism masquerading as authenticity. I’m talking about letting what you say you believe actually shape how you live in every context.

Jesus was many things, but compartmentalized wasn’t one of them. Read the gospels without your Sunday school filter on and you’ll find someone who was consistently, sometimes uncomfortably, himself. Overturning tables in the temple. Calling out religious leaders for their hypocrisy. Eating with tax collectors and prostitutes while the respectable people clutched their pearls. He didn’t have a “synagogue voice” and a “street voice.” He had integrity in the truest sense, the word means wholeness, being undivided.

When he said “let your yes be yes and your no be no,” he wasn’t giving communication advice. He was describing integrated living. Mean what you say. Say what you mean.

Being a Christian at work doesn’t mean you proselytize in meetings or put Scripture references in your email signature. It means you tell the truth even when a lie would be more profitable. It means you treat the intern with the same respect you show the CEO. It means you take responsibility when you screw up instead of blame-shifting. It means you’re known for keeping your word, serving others, and doing the right thing even when it costs you something.

That’s Christianity with its work boots on. And it doesn’t require you to announce it, people will figure it out on their own. If you have to announce it, well, you get it.

The beauty of the gospel, if you actually understand it (something I think I do until I read it again), is that it demolishes the need for multiple selves. God, I wish I had come to walk with Jesus seriously 13 years ago after that night in the ER. Grace means your worth isn’t earned in any room. You’re not performing for God’s approval, you’re not hustling for validation, you’re not code-switching to meet different audiences’ expectations. You’re a son. That’s your identity. Everything else is just context.

This matters for your kids in ways you might not realize yet. They don’t need to see faith as a religious performance you put on for church. They need to see it as bone-deep identity that doesn’t change when you walk out of the building. When your Christianity affects how you treat the server at dinner, how you talk about people who aren’t in the room, how you handle losing money or gaining it, losing a job or landing the dream role, that’s when they start understanding it’s real.

If your faith makes you more careful, more anxious, more image-conscious, more fragmented, you’re doing it wrong. And boy have I been doing it wrong. The gospel should make you more free, more bold, more yourself. Because if God’s acceptance of you isn’t based on your performance, why are you still performing?

This is the part where a lot of Christian men get lost. They mistake religious activity for spiritual integration. They go to men’s group, serve on a committee, lead a small group, all while being fundamentally the same fragmented, performance-driven, anxious men they were before. Because they’ve added Christianity to their life instead of letting it be what they build their life principles on.

What You Gain (And What You Lose)

Some relationships won’t survive your integration. When you stop performing the version of yourself that people have come to expect, some of them are going to be confused, uncomfortable, or even angry.

Let them go.

I know that sounds harsh, but relationships built on fragmented versions of yourself aren’t real relationships. They’re in love with a version of you that doesn’t actually exist. When you continue to fan those relationships you’re trading authenticity for approval, and it’s a terrible exchange rate. The people who stick around when you start being consistent, those are your people. The ones who can’t handle the real you were never really with you anyway.

When I told my close friends I was going to start a Small Business Coaching practice, not a single one said “that’s not a real thing,” or “but you have a family you can’t waste your time doing that.” Instead, my real friends asked how they could help, encouraged me, a few even asked if they could become clients. Tell your circle your true dream, see who is in line with the real you. It’ll startle you.

Some opportunities will close. New job opportunities that require you to compromise your values. Clients who want you to operate in ways that violate your integrity. Promotions that demand you become someone you’re not. These losses sting in the moment, especially when you’re watching someone else take the opportunity you walked away from.

This week I took a few interviews. On each one I told them my filters: I won’t be a road warrior. I won’t let someone dictate when I can take lunch. I will pick up my boys from school at least once a week, and there’s no way I miss the Christmas Parade. Some of those interviews were awkward because I was refusing to be who I’m not, and refusing to be a set version of what their employees must be. The interviews I’ve taken to the second round are with companies that loved that I stated that. That’s where the real Chance belongs anyway.

Every opportunity you decline because it requires fragmentation is an opportunity that would have made you more fragmented. You’re not losing something valuable, you’re avoiding something corrosive.

When you stop performing, people stop relating to your performance and start relating to you. The friendships that form around integrated living are different, they’re built on truth instead of shared facades. Your wife stops wondering which version of you she’s married to. Your kids stop trying to decode which dad is showing up today.

And at the end of your life, when your kids tell stories about who you were, they won’t remember your performance. They’ll remember whether you were the same person everywhere, or whether they spent their childhood trying to figure out which version of dad was real.

Give them the gift of consistency. Give yourself the gift of integration. Be yourself.

See what happens.

In your corner,

Chance

🔥